- Home

- Saul Tanpepper

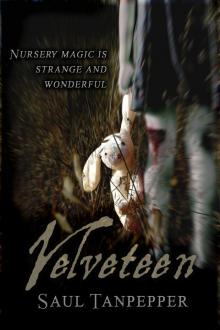

Velveteen

Velveteen Read online

C • O • N • T • E • N • T • S

VELVETEEN

Author’s Note

Excerpts

Care to share?

Copyright & License Notices

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Tanpepper Tidings Newsletter

(subscribe for updates and offers)

Craving more Tanpepper?

VELVETEEN

by Saul Tanpepper

©2013

All rights reserved

[email protected]

Subscribe for updates on new releases,

special (& exclusive) pricing events,

giveaways, signings, and more:

https://tinyletter.com/SWTanpepper

VERYONE WAS SICK in those days, after my baby brother died— Mama and Daddy. Miss Ronica.

Even me.

Especially me.

We were all sick, and we were dying.

They didn’t know it, but I did, though not till right near the very end. But long before that, I could smell it something terrible.

I remember, during one of those clear moments, right before it happened, when the fever wasn’t so thick in my head that I couldn’t think straight, I remember looking out my bedroom window onto the street and seeing it everywhere. Smelling it, the sickness.

Everyone was running, trying to escape. The neighbors, Mister Sam, who left his champion laying chickens to starve in their coops after he’d made such a fuss over them. Most people were running. Mama and Daddy, too.

But you can’t escape from what’s inside of you, no matter how fast you are or how long you run.

Later, looking out the car window on the day we tried to leave but couldn’t, you could tell they were getting tired by then. You could see it in everyone’s eyes, not wanting to give up.

All they had to do was stop. If they’d just stop, they’d get the cure. But they didn’t know that then, or didn’t want to believe it. Nobody did, and by the time I’d figured it out for them, it was too late.

there is no cure

Adults only believe what they want to believe and nothing else. That’s just the plain old truth of it.

I already knew about death, even before all of this happened. I knew because, like I said, it had happened to my little baby brother.

I don’t like thinking about it much, but I have to so I don’t forget.

The animals were first, days and weeks before the people. Even before the bat, I’m sure. I saw them being sick, though maybe I didn’t realize just exactly what it was yet. The signs were all around.

Mama and Daddy didn’t see them, or they pretended they didn’t. They were too busy fighting with each other to care anything about the animals. But I saw.

I saw.

sweet dreams, baby

I didn’t understand it at first. I was too scared like everyone else, right up until after Ben Nicholas died, which is when I finally knew it wasn’t just the people in my house or on my street or even just

a thing that happens

on this whole long island where we used to live.

Where did they all go afterward, the ones who got cured?

It’s been so quiet here for so long that I can hardly remember what my Mama’s voice sounds like anymore.

Only Daddy’s: Stay here, sweetheart. We’ll come back for you, I promise.

And the terrible sad sound of Mama’s crying when the door closed for the last time, just like after my little baby brother.

sweet dreams

After Ben Nicholas died, I . . . .

I couldn’t save him like I did me. It was too late, by then. But it doesn’t mean he’s gone forever. That’s what I realized. So I’ve been waiting

a long, long time

to make him Real.

I remember being afraid before I was better again. Afterward, walking to the cemetery to see my brother for the last time. No Mama or Daddy that time, just me. I wasn’t afraid no more. I wasn’t afraid because I knew how to fix things.

It’s strange. I remember being afraid, but I don’t remember the feeling of it, like watching a movie of myself with the sound turned all the way down. I remember thinking: Mama and Daddy are sick, and I’m sick. They’ll be better if they just stop running. But not me. If I stop, I’ll die. I was already too deep inside of myself by then and couldn’t speak on the outside no more, not even with my inside voice, because my tongue wouldn’t work. I couldn’t tell them what I was so afraid of.

Before Ben Nicholas died, I honestly didn’t want to live no more. But afterward . . . .

Well, everything changed afterward, didn’t it?

Mama and Daddy will come back for me, now that they know, too. After they get the cure.

I couldn’t just leave him like that.

So I fixed it. Fixed myself.

I’m not scared anymore. I’m not anything. Don’t feel anything, don’t remember what anything feels like. Being comforted or being frightened, for example. Just the memory of those things filling me. That’s part of what happens when you get better. It hollows you out. But I’m not sorry about it.

Still, sometimes, I just wish I could feel a little. Just a little tiny bit.

Hot or cold, happiness, loneliness. Even fear.

Anything.

Sometimes I even miss the hunger that used to eat away at me inside my mind until I thought it would swallow me up for being so big when I was just so small. Just to feel, I don’t know, something?

Right before I was cured, I could smell the infection inside my mama. I think she brought it home with her from the hospital. I could smell it on her skin, eating its way into her bones where it slept so quietly, pretending to not be there. I didn’t smell it in my father at first, but it came, later. Mama gave it to him, the disease. I’m pretty sure about that. Or maybe he took it for himself, like I did because

nursery magic is strange and wonderful

he knew he’d be left behind if he didn’t. He took the sickness and then went to get the cure.

The smell of the sickness about me and Ben Nicholas was the same, but it was different from their’s. Different from everyone else’s. And when Ben Nicholas died and stayed dead no matter how much wishing and crying I did, that’s when I knew I wouldn’t come back neither.

For us, Ben Nicholas and me, the sickness didn’t sleep inside like it did in Mama and Daddy. It didn’t wait and hide and pretend. Instead, it rose up inside of me, burning and biting. It raged and screamed until I finally — finally — understood why Ben Nicholas had acted the way he had on his very last day of life. The sickness chewed away at the insides of my head and grew big and dark and ugly, like one of those scary, angry, snapping dogs.

(Not Shinji, though; Shinji was never like that.)

It made me scream and bite at all the things outside of me with a crazy mad fury, and I was so angry all the time. Until I wasn’t angry no more.

I still wanted to bite then, but it was a different wanting. It was different because I was finally all better and had gotten my appetite back.

But even that, too, has faded away. I’m not hungry no more.

I’m so sorry, Ben Nicholas. I wish I had known sooner. I would have protected you better.

How long have I been standing here?

forever

I don’t know. The darkness here is everlasting. But I’ll stand here until Mama and Daddy come back for me. When it’s time. They’ll know. The door will open. Their arms will open. And we’ll all be together again. A family. All of us.

forever and forever and forever

together

That’s how it works, Ben Nicholas, because magic is

strange

the only thing

wonderful

that works anymore.

He’s waiting for me behind the shed, where I made a nice bed for him in the leaves, hid him beneath the board so nobody will be able to take him this time.

First thing’s first, honey.

Ben Nicholas.

I didn’t want Mama to bury you again in the dirt. Twice is too many times to be put into the ground. To be dug up. Twice is enough.

I bump against the wall for what seems like the millionth time, not even aware I’ve taken a step. I keep forgetting where I am. I step back with a sigh that sounds like

breathing

leaves rattling in the gutters.

I’m patient. I’m not going anywhere, waiting for

the door to open

Ben Nicholas to finish becoming Real.

A part of me wishes I could sleep. But I know I can’t. If I do I’ll never wake up. So I listen to the roaring silence inside of me instead. Like music. It keeps me from ever growing tired. The sound of it carries me along as if I was a wind over the ocean in a painting on the wall. Time and silence eat at my insides. They tear apart my memories until I find myself clutching at them with my mind as tightly as I used to hug Ben Nicholas in my arms. I don’t want to lose a single one of them, but I know some may already be

dead

lost. Some are fading. It’s okay, as long as I don’t forget the most important things:

Mama and Daddy.

Shinji.

Myself.

But most of all:

My dear sweet Ben Nicholas.

My poor little baby brother.

So I allow the memories to scratch and claw inside my head until they are raw and bleeding inside of me again. That’s what keeps them fresh.

Are there really such things as vampire rabbits, Daddy?

Only in storybooks, honey.

What about zombies? Are there zombie rabbits?

Zombies? No, honey. Not rabbits, only people. Now, shhh. Go to sleep. Sweet dreams, my baby.

“I wish you wouldn’t read her that silly story, Rame. Not right before bed. She’ll have nightmares.”

“What story?”

“Seriously? You’re going to play that game?”

“Oh, come on, Lyssa. Cut me some slack, it’s just a silly little kid’s book.”

I turn onto my side and bury my head in the pillow, trying to drown out the sound of my parents arguing. They said they weren’t going to. Mama told Daddy he could stay with us as long as they didn’t fight, and Daddy promised to try not to. But now they’re at it again and that means he’ll have to leave, and I don’t like it when he’s not here.

Nothing has been the same, not since Mama returned from the hospital a couple months ago, when my little baby brother died. He wasn’t but just two days old.

I wrap the pillow tight around my ears, but then I discover that it works too well. I really can’t hear a thing except for my own rapid heartbeat and a few of the louder words coming through as muffled sounds with no meaning. I don’t want to listen, but I also don’t want to not hear.

I can’t help myself. I slip off the bed and tiptoe over to the door. Squatting down behind it in a tight little ball, I hug my knees to my chest and rest my chin on them. My toes wiggle in the harsh yellow light that washes through the crack underneath the door. I try not to feel naughty for spying.

The arguing stops for a moment. I freeze, every muscle in my body aching. Did they hear me?

I hope they don’t come in to check. If they do, I’ll run back to my bed and dive beneath the covers and pretend to be sleeping. I’ll probably be breathing too hard and fast, though, and then they’ll know I’m really awake and was listening.

Would it make them stop arguing?

My breath is quick and warm on my arm. It tickles the hairs, making me shiver even though the air in my room is too hot and thick and close about me that it makes it hard to fill my lungs. But I don’t open my window. I won’t let in the cool air. There are things out there in the night, frightening things. Not vampires, which I know aren’t real, but other things which are.

We live in a different world now, Lyssa. I’m sorry, but it’s true. You’re not helping Cassie.

I close my eyes and lean my head against the door. It rattles slightly, but they don’t hear it. I let out a deep breath. They’re arguing again. About

him, even when it’s not

me.

“All I’m saying is that she doesn’t need to hear stories about blood-sucking rabbits.”

Daddy laughs. “It’s not a blood-sucking rabbit, Lyss. It sucks the juice out of fruits and vegetables and turns them white. I mean, come on! Millions of kids have read it, and I doubt it ever caused a single one of them to have nightmares. Besides, it’s Cassie’s favorite. Where do you think she got her rabbit’s name from anyway? You never asked her about that.”

“I don’t know! I just assumed the stupid thing already came with a name.”

Nothing for a moment. Then:

“I didn’t mean that. I’m sorry, Ramon. But I still don’t like it, that story. In fact, I don’t like most of the stories you choose for her. They’re always so . . . so dark and violent. We don’t need that right now.”

“Name one.”

“What about that book with the rabbits who have to leave their home?”

“Watership Down? Really? Okay, it has its moments, but, Lyssa, you’re overreacting again. You need to stop worrying about every little tiny thing.”

“I’m not worried about every little thing. I’m worried about Cassie.”

“She’s fine, honey. She’s not going anywhere.”

“You don’t know that! You don’t know what it’s like!”

“Lyssa, seriously. This is ridiculous. This week it’s make-believe vampire rabbits, next week it’s . . . what? Garden gnomes? You can’t protect her from every little thing.”

Silence floods the house, drowning me. I can sense their anger getting bigger, becoming an ocean. I can almost smell it, the saltiness of it. The walls soak it in. The bed in their bedroom smells of it.

Finally, Daddy: “Cassie’s not . . . . She’s not a baby anymore, honey. She’s strong and healthy. You need to let go of the idea that—”

“Don’t tell me what to do!”

“She’s a big girl, Lyssa, six — almost seven. She’s old enough to know the difference between what’s real and what’s make-believe. Do you?”

“Don’t you dare pull that crap on me, Rame. I may not be able to control what’s real all the time, but I can sure as hell control what’s not!”

bad words, mama

Daddy doesn’t answer. Or, if he does, I can’t hear it.

“Please, Ramon, I’m just asking you to read her something else. Is that so hard? There are so many other books, better ones. And if she insists on a rabbit—”

“You know she will.”

“Then read her Guess How Much I Love You.”

“Oh, jeez. Cassie’s too old for that.”

“I don’t care, Rame. Just find something else. I’m sick of hearing about vampires, even if they are rabbits.”

It was Daddy who brought Ben Nicholas home. He didn’t have a name at first, not for a while, because Mom was still in the hospital and it just seemed wrong to name him until she was home and we were a family again. But when she finally did come home, she wouldn’t even look at him. She wouldn’t, and it was all on account of my little brother was dead.

He came from the place where they both work, Daddy and Mama, the place where they fix animals and make them better than when they started off. Not the animal hospital, but the other place. Laroda Island.

A lot of people say that what they do out there is wrong. They say they turn animals into monsters. But Mama and Daddy tell me to ignore them. They tell me it’s not true, they wouldn’t do those kinds of things. They want to help people, not hurt them. That’s what they say, even if they can’t figure out how not to hurt each other.

>

Ben Nicholas was a fat little furry fuzz ball, his hair all poufy white, except for a single brown splotch on his belly, like he’d gotten into some mud outside and it never washed off. Or someone spilled chocolate milk on him, which I never did, although once some of my mint ice cream got on his foot, though Shinji licked it off. He’s also pink on his nose and his eyes are red like bubble gum. I always forget about them because the rest of him’s so white. I always just imagine him as a cloud in the sky with a little bit of brown.

I only saw my baby brother alive the one time, right after he came out of Mama’s belly, and I was looking at him through the window with the wires making X shapes in the glass because I was too young to go inside where they took him out of Mama, too small to wear the blue mask that Daddy and all the nurses and doctors had to wear. But that was fine by me, because there was a lot of blood on the doctor’s hands when he came out, though Mama didn’t seem to notice it or even be in any pain, although her face was shiny from sweat and white like the bed sheet. She just looked tired. Like she wanted to take a nap.

Miss Ronica was holding my hand, squeezing it. I must’ve squeezed back too hard, because she shook it and said, “Okay, that’s enough, Cassie. My fingers are numb.”

His skin was all icky blue and bloody, and there were ucky bits of it peeling off like candle wax.

“He’s not crying,” I said. “Little babies are supposed to cry right after they’re being born. That’s how they learn to breathe.”

He was just looking straight up at the lights in the ceiling of the hospital room and I could hear Mama asking for him and Daddy crying and laughing at the same time. But Remy — that’s what they had decided they were going to call him, which is short for Remington, like Grampa’s name — was very quiet. He didn’t make a single sound.

I think maybe I knew right then that something was wrong with him, though I didn’t say anything about it at all to anybody. I didn’t want to upset Mama or Daddy or Miss Ronica. I didn’t want to seem ungrateful for having a little brother, which I knew they were afraid I was. All that mattered to me was if Remy could help put our family back together again, and not like all the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t do for poor Mister Humpty Dumpty.

Open Wide

Open Wide Deep Into the Game: S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND (Episode 1) (Volume 1) (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND)

Deep Into the Game: S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND (Episode 1) (Volume 1) (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND) Shelter in Place: A short story from the world of BUNKER 12

Shelter in Place: A short story from the world of BUNKER 12 Iceland: An International Thriller (The Flense Book 2)

Iceland: An International Thriller (The Flense Book 2) GAMELAND Episodes 1-2: Deep Into the Game + Failsafe (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND)

GAMELAND Episodes 1-2: Deep Into the Game + Failsafe (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND) THE FLENSE: China: (Part 1 of THE FLENSE serial)

THE FLENSE: China: (Part 1 of THE FLENSE serial) S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND, Season One Omnibus

S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND, Season One Omnibus Golgotha: Prequel to S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND series (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND companion title Book 1)

Golgotha: Prequel to S.W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND series (S. W. Tanpepper's GAMELAND companion title Book 1) THE FLENSE: China: (Part 3 of THE FLENSE serial)

THE FLENSE: China: (Part 3 of THE FLENSE serial) Leviathan: A Short Story About the End of the World

Leviathan: A Short Story About the End of the World Insomnia: Paranormal Tales, Science Fiction, & Horror

Insomnia: Paranormal Tales, Science Fiction, & Horror Velveteen

Velveteen THE FLENSE: China: (Part 2 of THE FLENSE serial)

THE FLENSE: China: (Part 2 of THE FLENSE serial) Deadman's Switch & Sunder the Hollow Ones

Deadman's Switch & Sunder the Hollow Ones